GENRE: Rock

LABEL: Dead Oceans

REVIEWED: July 18, 2024

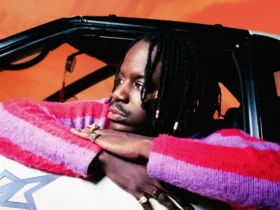

The New York singer’s smoldering, sophisticated songs get a little more cosmic while retaining their characteristic wit and charm.

In March 2022, Cassandra Jenkins was laid up with COVID at a Homewood Suites in Aurora, Illinois, drowning her sorrows in Wayne’s World while her tour bus drove on without her. It was a terrible time to get sick. Not long before, the lifelong musician had been ready to give up music altogether—or at least jettison hopes of ever making a real career of it—when her second album, 2021’s An Overview on Phenomenal Nature, unexpectedly connected with fans and critics. Now, quarantined in her hotel room, her mind spinning with worst-case scenarios, she began writing a song to keep anxiety at bay. “You know I’m gonna keep at this thing if it kills me/And it kills me,” she sang, in an early version of what would eventually become “Aurora, IL,” one of the standouts from her new album, My Light, My Destroyer. Determination and its flip side, desperation, are nothing new in Jenkins’ work. (“Give yourself a few years… None of them like you, dear,” she sang wryly on her solo debut, Play Till You Win.) But here, they take on almost cosmic dimensions, providing the backdrop to some of her most revelatory—and carefully rendered—songwriting yet.

“Desperation,” in fact, is the sixth word we hear on the whole record, in an opening line in which Jenkins tells us, in no uncertain terms, just how desperate she is. She recounts an existential search, nonspecific yet unmistakably real. As she reaches a climax in her quest, she sings, “And I felt my arms rise light as feathers,” her alto warmly reassuring over a sweet approximation of Van Dyke Parks-esque ’60s pop. But everything gossamer suddenly turns hard and brittle: “And the clock hit me like a hammer/And my eyes rolled back like porcelain/And the breeze cooled me like aspirin/And I cried.” You can practically feel each one of the objects she invokes beneath your fingertips.

The album is peppered with similarly dazzling images and unexpected counterpoints. In the slippery heartland rock of “Aurora, IL,” her sickbed spell leads her gaze upward, to planes crisscrossing the sky, and then even higher, to a vision of William Shatner circling the planet, weightless in one of Jeff Bezos’ rockets. Shatner weeps upon re-entry. Juxtaposed against this, she spins humdrum worry (“How long can I stare at the ceiling/Before it kills me?” goes the line in the final version) into a meditation on the precarity of the human condition.

She’s also just plain funny. Jenkins has always had a sneaky sense of humor—look no further than her fondness for unexplained Easter eggs. (After her debut album ended with “Halley,” a song about the comet, she slipped “Hailey,” a tribute to her friend Hailey Benton Gates, the actor/journalist/model, into the penultimate slot on An Overview on Phenomenal Nature; the new album closes with a lilting instrumental outro called “Hayley.”) On “Clams Casino,” a smoldering rave-up about loneliness inspired by her grandmother’s death, she contemplates leaving the hotel bar and driving out to the ocean, leading to an unexpected punchline. “I heard someone order the Clams Casino,” she sings. “I said, ‘Hey, what’s that?’ They said, ‘I dunno.’” It’s a joke so anticlimactic, you can almost imagine Stephen Wright intoning it in his trademark deadpan. Yet there’s tenderness here, too—the empathy of someone who knows what it feels like to be let down in a moment of need.

Once loosely rooted in Americana-tinged indie, Jenkins stretched herself on An Overview on Phenomenal Nature, experimenting with ambient jazz. Here, she pushes further into a switchbacking sequence of interstitial instrumentals and collaged field recordings. Some of these feel central to her themes: “Betelgeuse” captures a moment in which Jenkins and her mother, a science teacher, go star-gazing, pointing out Orion and the Moon. Her mother’s enthusiasm is infectious, and the feeling of looking up at the vastness of space, awed by the sprawl of all of those tiny pinpricks of light, will be familiar to anyone who has ever rolled out a sleeping bag in their suburban backyard. The collages don’t always work; “Attente Téléphonique,” a meandering spoken-word fragment in French, breaks up the flow of the album’s final third. But it’s nonetheless gratifying to hear Jenkins loosening up and pushing beyond the signposts she’s previously established for her sound—no more so than in “Petco,” a song about loneliness and regret (like so many on this album!) set to molten guitar tones that summon ’90s alt-rock and, particularly, the clean-lined pop-grunge of the Breeders. It’s an audacious shift in tone, but, thanks in part to her collaborators, it works beautifully. If only all grunge pastiches felt so natural and so fun.

Like “The Ramble,” her previous album’s closing song, “Only One” highlights Jenkins’ facility for understated sophistipop; she’s a masterfully silky interpreter of hurt, a canny channeler of failed love in the softest possible tones. But the album’s very best song is its most atypical. “Delphinium Blue” is mostly synths—per the credits, a dream lineup of Korg Poly 800, Yamaha CS15, Roland JX-03, Roland Alpha Juno, and more, plus a little fretless bass, from Spencer Zahn, to keep the whole thing well-oiled. It’s an unusually distilled sound, as though all of those keyboards had been fed, via a slow drip, into a clear liquid in a clear tube. Jenkins’ writing is equally concentrated. “I saw I missed your call/Sorry for not picking up/I got the job/At the flower shop,” she sings in the song’s first four lines. But if desperation—which is nothing but a particularly unruly form of desire—is the backdrop of the album, here she keeps that want coolly in check. Drop by drop, she fills in just enough details to complete the picture of her determined protagonist, who intones motivational mantras to herself in a soft, meditative purr: “Chin up/Stay on task/Wash the windows/Count the cash.” Jenkins has never wielded a more finely tipped pen than when she offers us the image of night falling “like thorns/Off the roses,” or her protagonist methodically snipping stems, keeping cool in the walk-in. Over a backdrop that sounds like Enya scoring a David Lynch film, Jenkins paints an exquisitely detailed picture of desire and control. Scissors in hand, eyes fixed on the fogged glass, she keeps the tumult of unchecked emotion at bay.