Emo Rap Returns — And the Cycle Starts Over

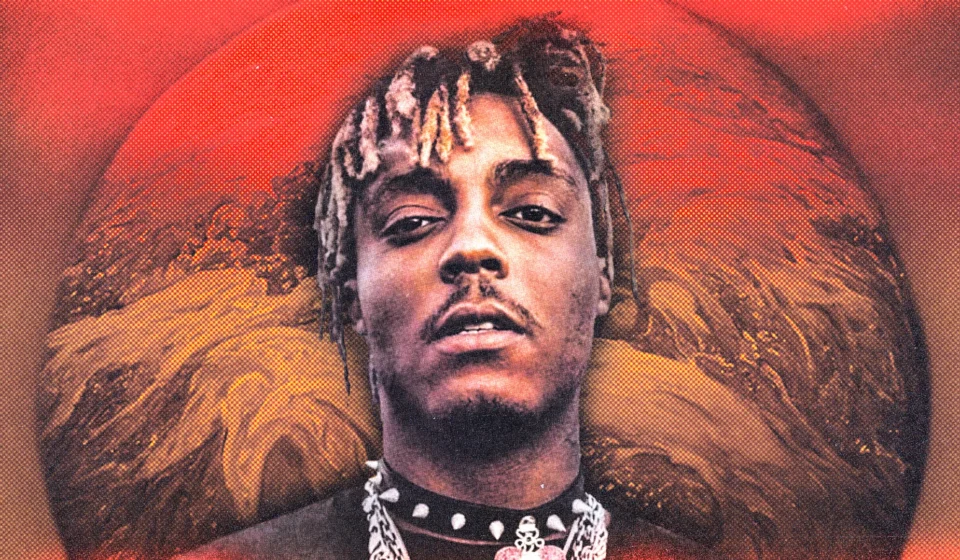

In a recent performance clip circulating online, a 20-year-old rapper from Asheville, North Carolina stands centre stage with black-painted nails, dermal piercings set into his face, and locs hanging low over his eyes. The artist, known as TopOppGen, delivers a track called “21 Club” — a song steeped in homage to Lil Peep, XXXTentacion, and Juice WRLD, three figures whose lives were cut short before or at the age of 21 and who later became pillars of emo rap’s mythology.

The song follows the subgenre’s blueprint almost too faithfully. A mournful guitar loop reminiscent of late-2010s emo trap production. Fragile, strained melodies. Themes of dependency, jealousy, and emotional volatility. Lines that reference substance abuse, depression, and death with unnerving directness: “I do drugs and blackout / My girl gotta make sure that I’m breathing.” What lingers afterward isn’t the strength of the songwriting, but the sense that the aesthetic itself is doing the heavy lifting.

Before emo rap hardened into a recognizable commercial image — damaged young men self-medicating, alienated from the world, and betrayed by lovers — the term was far looser. It once described emotional extremity across hip-hop more broadly: the paranoia and nihilism of Queensbridge street rap, the haunted minimalism of Southern horrorcore, the cold isolation of early Chicago drill, the emotional drift of internet collectives that blurred rap with ambient melancholy, and the raw vulnerability of Southern pain music. Kevin Gates once captured this complexity perfectly when he framed his emotional isolation not as softness, but as misunderstood intensity — pain surfacing through aggression, confusion through pride. That nuance, that internal contradiction, once defined emo rap at its best.

As someone who’s never been especially fond of the genre’s mainstream form, there’s still one project from that era that holds up: Lil Peep’s Crybaby. Released in 2016, it felt grounded in lived experience rather than shock value. There was friction between escapism and despair, between wanting pleasure and being swallowed by addiction. It felt human. But once emo rap fully entered its branding phase — built around spectacle, self-destruction, and martyrdom — the music itself became secondary. By the late 2010s, fatalism had become a selling point, with artists openly mythologizing early death as destiny.

Looking back now, that moment reads less like rebellion and more like a warning. When deeply personal trauma is repackaged for mass consumption, the results can turn ugly fast. And now, enough time has passed that a new generation — raised on the iconography rather than the context — seems ready to reenact it all.

TopOppGen appears to be one of those artists. He was barely a teenager when emo rap’s original figureheads died, and his growing catalog reflects a fixation on the wrong takeaways. His music is already drawing millions of listeners, placing him well above most underground peers. That visibility makes his work difficult to ignore, even when it’s deeply unsettling. On “Fake Pills & Real Scars,” he declares, “I’m not Lil Peep, but I’m tryna go out like him,” echoing the cadence and emotional pitch of artists whose legacies were shaped as much by tragedy as talent. It often feels as though the end goal isn’t artistic growth, but eventual mythmaking — the idea of being remembered more for damage than craft.

Yet beneath the provocation, there’s something undeniably alive in how he captures the emotional chaos of young love. His writing often resembles exaggerated teen drama — raw, awkward, unfiltered — but he commits fully to the feeling, embarrassment and all. On tracks like “drivemeinsane,” he teeters between tenderness and fixation, sounding like someone unraveling in real time. “Cute Like Aspen,” a warped love song aimed at another rising artist, channels the energy of early digital-era romance tracks, filtered through pills and paranoia. Romance, for him, is never stable — it’s intense, consuming, and doomed.

That intensity quickly turns darker. Like several of his influences, obsession mutates into control. On “Petty $hit,” he pairs heartbreak with violent possessiveness, threatening harm as proof of devotion. On “suicide song,” he crosses an even more troubling line, recounting relationship violence in a way that frames himself as wounded rather than accountable. Whether fictional or autobiographical hardly matters — the narrative weaponizes harm as emotional credibility.

What’s most revealing is how consciously this persona seems constructed. Gen appears acutely aware that the rise of certain artists was fueled not just by their talent, but by their volatility. He leans into those traits because he believes they’re what define generational figures. But in chasing that mythology, he often forgets the basics: making music that stands on its own.

When he slows down and lets genuine emotion take the lead, the results are far stronger. Tracks like “end up dead” tap into the introspective melancholy of Southern melodic rap, while “dirty cup” gains depth through collaboration with another troubled vocalist whose writing carries more lived-in reflection. In those moments, Gen’s limitations become clearer — next to artists who translate pain into clarity, his work can feel hollow, more costume than confession.

Listening to music that truly resonates tends to spark connections — memories, references, emotional echoes. That doesn’t happen as often here. Instead, the focus drifts outward, toward lore, controversy, and persona. That realization crystallized after watching an interview where Gen was asked about the music that shaped him. After a long pause, he shrugged and said he never really listened to music growing up. It might’ve been an attempt at mystique. But the unsettling part was how believable it sounded.

And maybe that’s the real issue. Emo rap is back, but for some of its newest disciples, the music feels secondary to the mythology — a loop of aesthetics chasing ghosts, repeating a story we’ve already seen end badly.